Much of the recent interest around the study of the material culture of American religion has been stimulated by project scholar Colleen McDannell in her Material Christianity: Religion and Popular Culture in America (Yale University Press, 1995). In the introduction, excerpted here, McDannell challenges traditional assumptions about American religious life by reading closely a Farm Security Administration photograph (similar to those she will examine in her book for the Material Religion project).

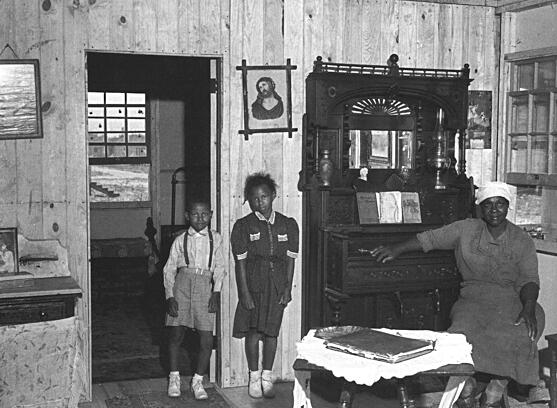

In June 1941, Jack Delano took a photograph of the interior of a home built by the Farm Security Administration. The family who lived in this prefabricated house had to leave their original residence because the army wanted the space for military maneuvers. We do not know anything else about this family except what we can see in the photograph. We cannot even be sure how to read the photograph, since we do not know how government photographer Jack Delano influenced the composition of the picture. Did he purposely pose the children under the Ecce Homo lithograph? Did he coax the older woman to place her arm spontaneously across the parlor organ?

For all that we do not know, what we can confidently say about this family is that they lived in a house that displayed traditional Christian objects and iconography. On the far left, sitting on a dresser is a reprint of The Infant Samuel. The original, painted by Sir Joshua Reynolds in 1776, is owned by the Tate Gallery in London. Above the children is a framed portrait of the head of Christ surrounded by a crown of thorns. It is very similar to an Ecce Homo painted by Guido Reni in 1636-7 that hung in the Dresden Gemäldegalerie until it was destroyed during World War II. The suffering Christ is balanced by a calendar with a print of a little girl playing ball with a dog. The dominant object in the photograph is a Victorian parlor organ, festooned with knickknacks and a kerosene lamp. Three books lie on the organ: Revival Hymns, Gospel Hymns, and one with no cover. Above the Infant Samuel may be a chromolithograph of the Holy Family of Jesus, Mary, and Joseph, but the print is overexposed and the images are difficult to make out.

This photograph visually demonstrates an overlooked dimension of American Christianity: the material dimension. This family, as well as other American families, placed in their home pictures and furniture with religious connotations. American Christians, this book argues, want to see, hear, and touch God. It is not enough for Christians to go to church, lead a righteous life, and hope for an eventual place in heaven. People build religion into the landscape, they make and buy pious images for their homes, and they wear special reminders of their faith next to their bodies. Religion is more than a type of knowledge learned through leading holy books and listening to holy men. The physical expressions of religion are not exotic or eccentric elements that can be relegated to a particular community or a specific period of time. Throughout American history, Christians have explored the meaning of the divine, the nature of death, the power of healing, and the experience of the body by interacting with a created world of images and shapes.

People learn the discourses and habits of their religious community through the material dimension of Christianity. By singing Gospel hymns and looking at pictures of the tortured Jesus, this African American family internalized a set of religious ideals. They practiced their religion, as one would practice the piano in order to become a competent pianist. The symbol systems of a particular religious language are not merely handed down, they must be learned through doing, seeing, and touching. Christian material culture does not simply reflect an existing reality. Experiencing the physical dimension of religion helps bring about religious values, norms, behaviors, and attitudes. Practicing religion sets into play ways of thinking. It is the continual interaction with objects and images that makes one religious in a particular manner. Each of the case studies presented here demonstrates how the material dimension of Christianity may be used to decipher the meanings of religious life in America. Studying material Christianity lets us see how the faithful perpetuate their religion day in and day out.

Let us look again at the photograph taken of the African American family. In this household, the sacred and the profane are not clearly defined as Durkheim would predict. Christian images are placed throughout the room. There is no evidence that any devotional activities take place near the pictures; we see no candles or altars. The religious prints are decorative elements, like the calendar art at the far right. On the other hand, the prints are explicitly Christian in nature; they are not merely representations of the natural order. Their content indicates a privileged supernatural order and its involvement with humankind. The Ecce Homo vividly displays the Passion of Christ and his sharing of bodily pain with humanity. The Infant Samuel, placed at a level easily seen by children, encourages devotional piety among the young. Framing heightens the prints' special quality and separates them from the calendar art. This family did not make rigid distinctions between religious pictures as ornamentation, devotional focus, or instructional media. They combined religious beliefs with the material culture of everyday life.

The parlor organ also reflects the integration of the church with the home. Prominently displayed on its music stand are hymn books. We do not know if the family ever sang the hymns, but we do know that they did not hide them under the table when the photographer arrived. The organ signals social standing and taste as well as religious sensibilities. As a popular instrument among the Victorian middle class, it came to symbolize family commitment to domestic and cultural values. If the household had the organ since the late nineteenth century (when it was probably built), it testifies, as any antique would, to the family's longevity. If the organ was recently purchased, it demonstrates a substantial financial investment. Christian commitments, musical taste, economic achievement, and domestic stability - none of these elements can be easily separated from the other.

The photograph also complicates our notions about the distinctions between "weak" Christians and "strong" Christians. Are these "weak" Christians who need images because they cannot cope intellectually with biblical truths? Given the social and economic condition of many African Americans in the 1940s, it is not surprising that the woman in the photograph wears a soiled dress and has legs so swollen that she cannot lace her shoes. We might conclude that the woman and her children do not have adequate access to religious education and facilities that would teach them "appropriate" ways to integrate "tasteful" art into their home in order to cultivate "authentic" Christian beliefs. That might explain why they include standard Protestant iconography (The Infant Samuel) with Catholic images of Christ (Ecce Homo). On the other hand, perhaps these are "strong" Christians who recognize that a picture of Christ is merely a picture and can never have any further meaning. They know that the print of the infant Samuel is only for instructing their children and that the organ is for singing Gospel hymns, not displaying wealth. They might even embrace all of the Victorian values that Kenneth Ames sees embodied in the nineteenth-century parlor organ: the moral superiority of women, the importance of domesticity, the display of material wealth, the maintenance of amiable social relations. The photograph leads us to suspect that there is no simple division between "strong" and "weak" Christians.

While we can speculate on the meaning of organs and chromolithographs based on how they are used in other households past and present, we are limited in what we can say about this family. Without the reports of others who knew the family or their own words, we are left to draw shaky conclusions about the meanings of the prints and the organ. When no words are available, it is too easy for us to read our own words into the material representation. Because this African American family living in Virginia in 1941 may not necessarily have the same set of values as the Victorian Protestants who played parlor organs or as the eighteenth-century Anglican artist who painted the Infant Samuel, this photograph cautions us against making unsubstantiated generalizations based on images. While words too must always be questioned, we need them in order to make at least partial sense out of the religious experience of this family. Just as the organ is metaphorically transformed into a producer of words when hymns are sung, so we must find ways to let mute objects speak. Spaces, architecture, and art do not convey information by themselves, they are activated by either their users or the scholars who are trying to interpret their meanings. The image cannot stand alone; it must be a part of a human world of meaning in order to come alive.

Copyright 1995 by Colleen McDannell, used by permission

Return to the electronic journal page

Return to the project home page